CSUMB Magazine

Toward a Brighter Future

When Eduardo M. Ochoa came to Cal State Monterey Bay as its president in mid-2012, he looked beyond the boundaries of his new campus to assess the challenges ahead.

“What I found when I came to CSUMB was that we had a remarkably diverse student body for a residential campus that in fact matched the ethnic composition of our service area,” Ochoa told the Chronicle of Higher Education in an interview conducted earlier this year. “But on the other hand our county … had an education level that was far below the state average.”

“Too many underserved communities were not succeeding in getting their young people through to high school graduation and being college ready,” he said.

“So we felt, if we were going to advance our access mission beyond where we were, we needed to reach down into earlier stages of the educational pipeline and partner with our K-12 colleagues.”

During his two-year tenure in Washington, D.C., as assistant secretary for postsecondary education, Ochoa had learned about the successes of Strive Networks – community-based collaborative initiatives whose goal is to improve outcomes at every step of the so-called cradle-to career pipeline.

I believe we are all here because we want every child in Monterey County to have access to an excellent education— Margaret D’Arrigo

Now, the local version of that initiative – called Bright Futures – is producing tangible results in Monterey County.

Its mission is to ensure that every child is prepared for school, succeeds inside and outside of school, completes a post-high school credential and enters a promising career.

Highlighting bright spots

In January, local partners in Bright Futures held a forum at CSUMB @ Salinas City Center to highlight educational success stories from around the county. The event brought together representatives of education, government, business and non-profit groups, all of whom are playing a part in the Bright Futures collaboration.

“I believe we are all here because we want every child in Monterey County to have access to an excellent education,” said Margaret D’Arrigo, vice president of community development for Taylor Farms, in opening the session.

The event highlighted bright spots, measures by which area schools were showing significant ongoing progress on a number of education measures. Participants were encouraged to look at displays which highlighted initiatives that were producing results at specific schools.

“We spend a lot of time focusing on the achievement gaps that exist. But we also need to take the opportunity to celebrate the accomplishment that are being made,” said Romero Jalomo, vice president of student affairs at Hartnell College, which has been an active partner in Bright Futures.

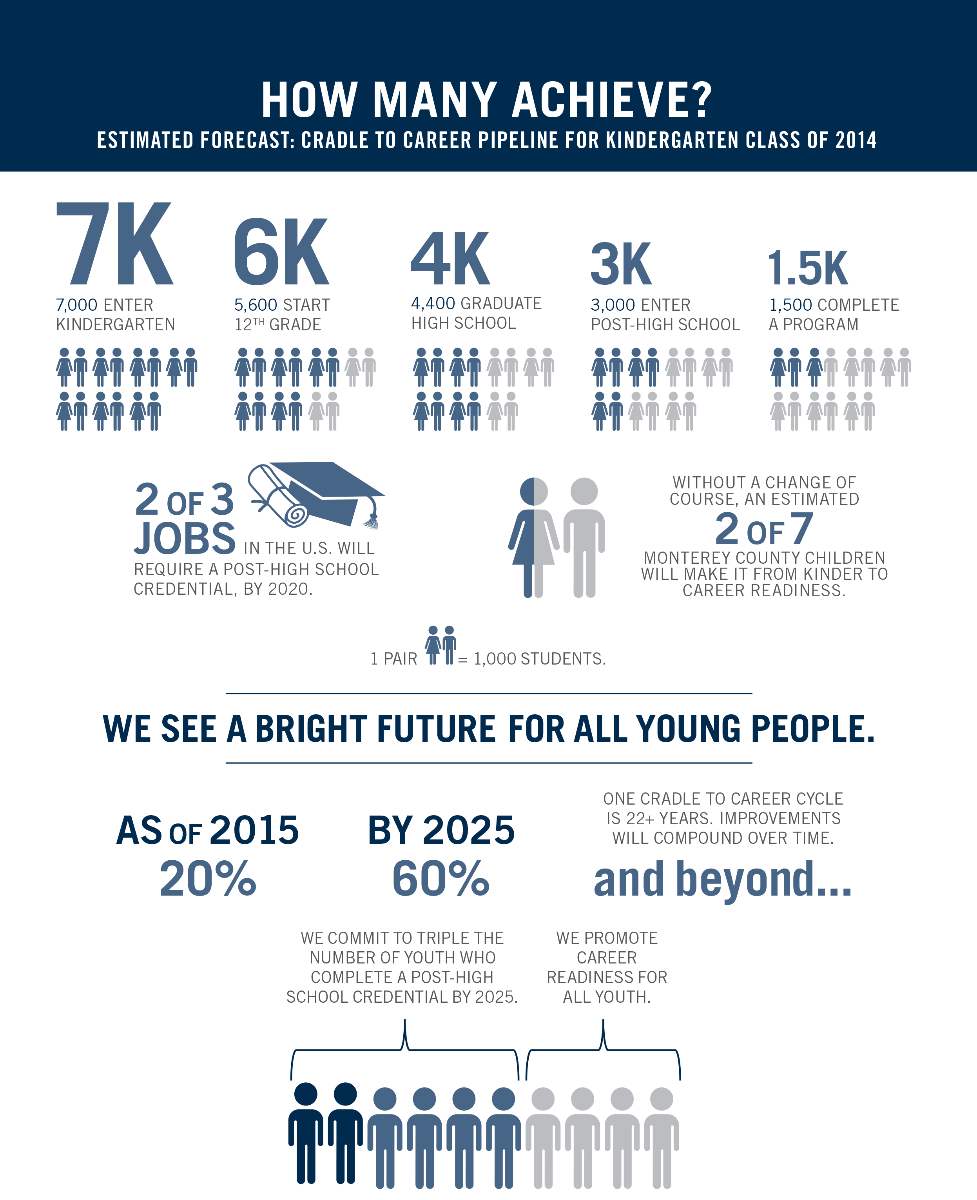

How many achieve? Estimated forecast: Cradle to career pipeline for kindergarten class of 2014.

- 7,000 will enter kindergarten

- 6,000 will start 12th grade

- 4,400 will graduate high school

- 3,000 will enter post-high school

- 1,500 will complete a program

2 out of 3 jobs in the United States will require a post-high school credential by 2020, but only 2 out of 7 Monterey County children will be career ready without a change of course.

We see a bright future for all young people. In 2015 only 20% of all youth will earn a post-high school credential; we want to improve that to 60% by 2025. That would triple the number of youth who complete a post-high school credential by 2025 and promote career readiness for all youth.

One cradle to career cycle is 22+ years. Improvements will compound over time and beyond.

All kids can learn

Cynthia Nelson Holmsky, director of Bright Futures, explained that her team, led by Michael Applegate, has built a “bright spots finder,” a computer program to analyze all public data about each grade level, classroom and subject countywide. The program looked for measures on which specific grades at each school were exceeding county and state averages for their peer group and had shown steady improvement of 10 percentage points or more over a three- year period.

“We were saying to ourselves, what if we only get two (bright spots) in the whole county? So when it returned more than 500 bright spots, we were thrilled. It was a big moment,” said Holmsky, who has directed the Bright Futures effort since it began in 2014.

What made the findings even more encouraging was that more than half of the bright spots came from schools that fell in the lowest economic quartile.

“There is the belief that you can’t break above these very low levels of performance (in low-income districts),” Holmsky said. “This completely changed that narrative because some of the bright spots are outpacing the state of California by 40 percent, with those very same poor kids. So we were very excited to use the data to challenge that set of assumptions and hopefully we can change the narrative to the idea that all kids can learn, that all kids respond to high expectations.”

Successes in Alisal

Among the districts whose accomplishments were highlighted at the event was the Alisal Union School District, located in East Salinas.

In Alisal Community School, where 96 percent of the students are classified as economically disadvantaged, former English language learners are now outperforming the state average for all students in English/Literacy by 34 percentage points and scores have increased by 32 percentage points over three years. The same students are outperforming state averages in math by 11 percentage points and have increased scores by 17 percentage points over three years.

Data is in every conversation we have and in every meeting we host.— Cynthia Holmsky

The event highlighted the three pillars of Bright Futures. First is the use of data, not anecdotes, to determine what works in the classroom. Second is the sharing of information about classroom successes to encourage collaboration and change. And, third is reinforcing the message that, to be truly effective, educational changes must impact students from all income levels and ethnic groups.

“It’s the power of collaboration. That is really the spirit of Bright Futures,” Holmsky said. “We don’t add a lot of resources. Rather, we engage existing resources in new and innovative ways.

“Many organizations are working on improvement, but are doing it in isolation. We’re just saying ‘Hey, let’s share the same goals, share resources so we can achieve more improvement together. By connecting those dots, a lot of change is happening.’”

Collective impact strategies

Bright Futures, and other similar efforts nationwide, embody what is called a collective impact strategy. A 2011 article by John Kania and Mark Kramer on collective impact in the Stanford Social Innovation Review cited the example of a Strive Network in Cincinnati, which brought together community leaders behind a common goal.

“These leaders realized that fixing one point on the educational continuum – such as better after-school programs – wouldn’t make much difference unless all parts of the continuum improved at the same time. No single organization, however innovative or powerful, could accomplish this alone. Instead, their ambitious mission became to coordinate improvements at every stage of a young person’s life, from ‘cradle to career.’

“Strive didn’t try to create a new educational program or attempt to convince donors to spend more money. Instead, through a carefully structured process, Strive focused the entire educational community on a single set of goals, measured in the same way.”

Bringing people together

Tim Vanoli was engaged with Bright Futures in its early days when he was superintendent of the Salinas Union High School District, and is now working with the initiative as superintendent of Soledad Unified School District.

“I think it is a terrific effort. It brings people together to share best practices and learn from what each other is doing,” Vanoli said. “It is very comprehensive. It is closely aligned with most of the educational initiatives that we are all really focusing on,” pointing in particular to college and career readiness measures.

California's new education accountability system includes the California School Dashboard, designed to allow the public to monitor school performance. One of its measures is college and career readiness, which is also a key factor for Bright Futures.

The big goal

An estimated two-thirds of all jobs will require a post secondary credential by the year 2020. The big goal of Bright Futures is, by 2026, to raise the percentage of Monterey County students who earn some type of post-secondary credential – an associate’s, bachelor’s or higher level degree or certificate – from the current estimate of 20 percent to 60 percent.

We engage existing resources in new and innovative ways.— Cynthia Holmsky

“With their new standards, the state of California has reconciled the fact that to graduate high schoolers without the (educational) rigor to go with it, is just not enough. Students need to be career-ready,” Holmsky said. “Technology is now part of every industry. Career technical education is no longer woodshop. It is high-impact, high- tech, so that needs rigor in high school, too. “

As the largest Monterey County employer, the agriculture industry has a growing need for more technically proficient employees.

“We really look at this (Bright Futures) as a way we are helping to build our future workforce,” said D’Arrigo of Taylor Farms. “We are generating a lot of data, and having people who can analyze that data and keep up with the technology is very important to us.”

Are they prepared?

The California Department of Education considers high school graduates "prepared" when they have earned a diploma and achieved at least one additional criteria, which include meeting standards in English language arts and mathematics, earning a passing score on two Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate exams or meeting the course requirements for college admissions, among others.

To reach its big goal, Bright Futures has worked with education, business and community leaders to develop its own list of specific measures at all stages of the education- to-career pipeline to monitor and, they hope, continue to improve.

“Data is in every conversation we have and in every meeting we host,” Holmsky said.

The factors include access to affordable child care, measures of kindergarten readiness and language, literacy and critical thinking skills at key grade levels. The initiative is also tracking the percentages of high school students who fill out financial aid forms and complete core classes necessary to attend college, as well as the numbers who earn a post-high school credential and enter a promising career.

The plan is to monitor key pieces of data connected to each measure, as the initiative advances on its goal.

That, too, can pose a challenge. Monterey County includes 24 different school districts. Hartnell’s Jalomo points out those districts “don’t always speak the same language; they don’t have the same systems for reporting data.”

At the same time, Jalomo said the partners – from all sectors – who have joined the effort are working hard to make a difference.

“I think that Bright Futures has been perceived in a very positive way by the community. A lot of different people are coming to the table in a very authentic way to share their good ideas,” Jalomo said.