CSUMB Magazine

Seas of Change

CSUMB faculty and student researchers traverse the globe

Two oceans. Two extremes. Two environments. The first filled with wide expanses of ice and freezing wind under a faded, colorful sky. The second filled with warmth and crystal-clear water under a blazing hot sun. Both teem with life. Both remote, thousands of miles from modern civilization. Both ideal for research.

Kerry Nickols, an assistant professor of marine science, and Brooke Morgan, a senior majoring in marine science, traveled the oceans for thousands of miles last summer, researching marine life and seeing first-hand the impacts of human activity on our planet. Each traveled by ship to get to their respective destinations.

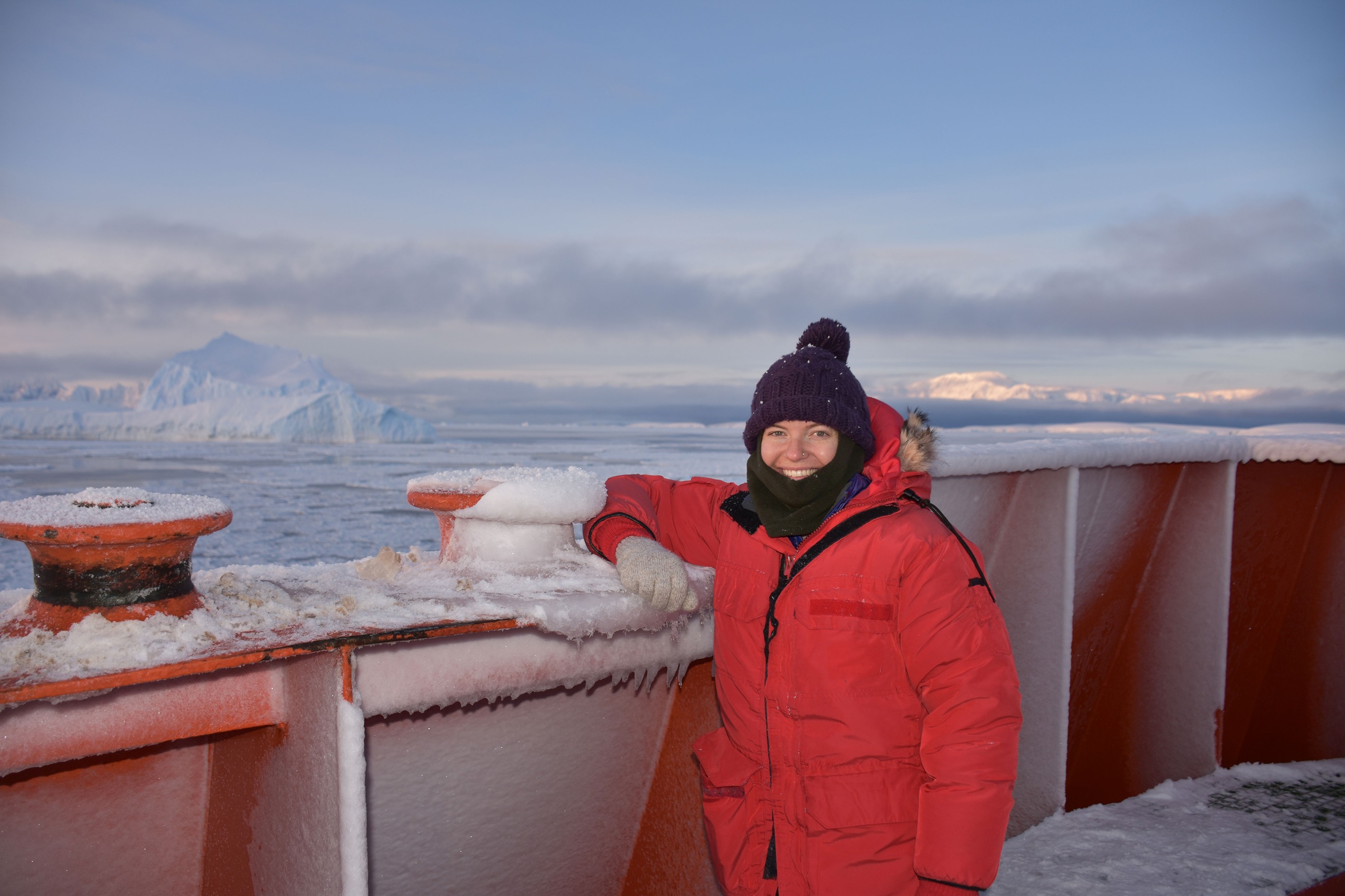

Nickols shared the deck with fellow scientists on her ship as it plowed through ice before arriving on the frigid shores of Antarctica. Once there, Nickols’ research focused on plankton behavior and distributions and how it may be impacted by rising water temperatures. Morgan sailed through tropical waters to the Phoenix Islands, a largely unexplored region of the South Pacific, where she and fellow students studied coral reefs, collected samples and developed policy plans for the region’s future protection.

Research on the ice

Nickols began her journey in Chile, spending one week at sea before her ship, the RV Laurence M. Gould arrived at Palmer Station, situated between glaciers and cliffs on Anvers Island in the West Antarctica Peninsula. The station, one of three permanent U.S. research stations on Antarctica, is only accessible by water. It can house 20 scientists and research personnel during the Antarctic winter (our summer) when Nickols called the station home.

The station is composed of two main buildings and several smaller structures. It houses laboratories, indoor aquarium tanks, a cafeteria-style kitchen, communal bathrooms and dormitory bedrooms. Outside temperatures averaged -10 degrees Celsius, or 14 degrees Fahrenheit. Winds could reach 70 knots, or approximately 80 miles per hour. During the Antarctic winter, the sun is up for three to four hours a day.

Nickols loved every minute of it.

“We worked under a sky that was filled with the colors of sunrise or sunsets,” she said. “Underneath that beautiful canopy, you had glaciers and enormous mountains rising up next to the ocean. It was stunning.”

Nickols was a part of the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Advanced Training Program in Antarctica for early career scientists. The international program, open to all nationalities, emphasized integrative biology for the course that Nickols participated in, using a combination of laboratory, field and ship-based projects. Nickols and her colleagues were offered the opportunity to study a wide range of Antarctic organisms and several different levels of biological analysis, such as molecular biology, biochemistry, physiology, ecology and evolution.

Nickols focused on the study of plankton and how they are affected by changes in temperatures. The pristine environment housed an ideal place for Nickols to do her research. “Climate change is happening rapidly – we are seeing it first hand in places like the West Antarctic Peninsula,” she said.

According to the Earth Institute at Columbia University, temperatures on the West Antarctic Peninsula have been warming at approximately 0.5 Celsius, or nearly one degree Fahrenheit, per decade since the early 1950s. The glacier on Anvers Island near Palmer Station has been shrinking approximately seven meters, or just under 23 feet, per year.

And that’s what we know from the ice melting above. As Nickols points out, it’s much more difficult to measure the ice melting from below due to rising water temperatures.

Melting ice is critical for plankton and other marine life. Ice provides a place for plankton to bloom and thrive. This plankton is eaten by krill, small shrimp-like creatures that are the main food source for penguins, whales and seals. The entire food chain is affected.

Nickols and colleagues studied plankton firsthand by utilizing the indoor aquarium tanks at Palmer Station. The tanks were connected to the sea outside by an intake valve. Nets that collected specimens were changed at sunrise and at sunset. This was done every day for approximately a month.

Krill also were a main focus of study. Together, the group tested impacts of increased temperature on krill from molecular up to ecological processes, and found indications of temperature effects on this important organism.

Nickols and her colleagues plan to publish some of their findings, and hope to conduct follow-up studies. She is looking forward to the possibility of another trip south. “I fell in love with the place,” Nickols said.

Living laboratory in the tropics

Photo by: Brooke Morgan

Thousands of miles from the ice of Antarctica, in the balmy waters of the South Pacific, is the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA). The PIPA covers an area about the size of California and is considered one of the last remaining coral wildernesses on Earth. It’s rarely visited.

That’s where Morgan and 22 fellow students from other universities headed last summer, living aboard a 135-foot sailing ship, the SSV Robert C. Seamans, for six weeks. Beginning their journey in Hawaii, they were accompanied by research divers from the New England Aquarium, scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and faculty from the Sea Education Association (SEA).

The work began before arrival to the research site. They were living on a working sailing ship. It was all hands on deck.

“Everyone had two six-hour watches a day. You were in the engine room. You were rigging the sails. When you weren’t taking care of the ship, you were in the lab,” said Morgan. “Sailing is physically demanding but it was amazing. You are completely disconnected. No internet. The only connection was with your shipmates. At night, you see countless stars blanketing the sky and touching the horizon. You really have time to reflect.”

Photo by: Brooke Morgan

The crew didn’t see land for two weeks, crossing the equator as they sailed approximately 1,600 miles of open ocean. Once they arrived at their destination, they anchored offshore of Orona, an atoll in the Phoenix Islands region. Sized at approximately two square-miles, the remote atoll surrounds a shallow lagoon filled with an abundance of sea life.

“In the shallow waters of the lagoon, we observed giant clams, young reef sharks and an abundant amount of fish of all kinds. The giant clams were all colors and patterns, and covered the rocky substrate of the reefs,” Morgan said. “It was vibrant, collected chaos.”

Highs and lows

Morgan and her fellow students had heartening and disheartening observations. The positive was the coral. The coral in the Phoenix Islands region was rebounding after coral bleaching was observed by a scientist in 2015. Bleaching occurs when the water is too warm. Corals expel the algae living in their tissues, causing the coral to turn completely white. The coral is not dead but it’s under more stress and subject to mortality. According to the National Oceanic Atmospheric Association, in 2005, the U.S. lost half of its coral reefs in the Caribbean in one year due to a massive bleaching event.

The negative was, on a remote atoll in the South Pacific, thousands of miles from the nearest continent, the students observed heaps of trash and plastics washed ashore on the beaches. “It was shocking to see common trash – shoes, shampoo bottles and toys – piled on the white sands of such a pristine, remote environment,” Morgan said.

Documenting sea life

Back on the ship, Morgan and her fellow students went to work. The crew began collecting water samples and specimens from a total of seven coral atolls in the Phoenix Islands region. Water samples were analyzed for salinity and alkalinity, the latter a measure for how a water body can neutralize acidic pollution from rainfall or basic inputs from wastewater. Samples of plankton were also collected, along with krill. “Since so little was known about the Phoenix Islands region, we were simply documenting sea life to get an idea of the abundance and diversity of the area,” Morgan said.

This research went for three weeks before the expedition ended at American Samoa. It was the trip of a lifetime for Morgan and her fellow students.

“I am humbled by the fact that very few people have visited this part of the world – and we experienced it,” said Morgan. “From an academic point of view, the on-site research was invaluable. But in some ways, the life lessons, especially the teamwork needed to run a sailing ship across the Pacific, were just as important.”